Welcome to the Korean Performance Research Program (KPRP) at Ohio State. The KPRP takes a leading role in convening innovative research into Korean and Korea-related performance traditions as they flourish in a global context. The KPRP was founded in Spring 2014 with the goal of promoting international appreciation and promulgation of the art and philosophy of Korean performance. Begun with the generous support of Dr. Chris Lee of Columbus Ohio, the OSU-KPRP envisions interdisciplinary education, research, and outreach with Korean performance tradition as leading inspiration.

Building on our unique strengths in traditional performance, we also engage with Korean popular culture as a recent outgrowth of long-held indigenous cultural expression. The Korean Performance Research Program is a crucial component of the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures’ unique curricular focus in East Asian performance traditions.

Program activities include hosting artists-in-residence and performance tours, conducting workshops and festivals, academic conferences and symposia, and publications.

A performance tradition is a collective expression of life histories. With a 5000 year cultural formation and exchange with the neighboring cultures, Korean performance came to manifest the characteristics of Korean ethnicity, experience, and place. The country was largely ruled by monarchic lineages over strict social hierarchy until the beginning of the twentieth century.

Korean musical traditions are therefore distinguished between court music for royalty and aristocracy, and folk music for the masses. Designated as Korea’s Intangible Cultural Asset No. 1, Korean court music typically manifests Korea’s dynastic grandeur and Confucian austerity that legitimized the ruling principles of Korean society for much of its history. Korean folk music on the other hand developed as a poetic outlet for the working class. Songs accompanied fishermen at sea, farmers in the field, workers at building sites, and vendors in marketplaces. Women, whose lives were a series of never-ending domestic labor and prayers for the wellbeing of their households, were equally passionate singers of life. From different regions of the Korean peninsula there remain songs of life, death, prayers and thanks for a bountiful harvest, to name just a few. It is worth noting that most Korean shamans, whose jobs are mediation between the human and spiritual worlds through the use of song and dance, are women.

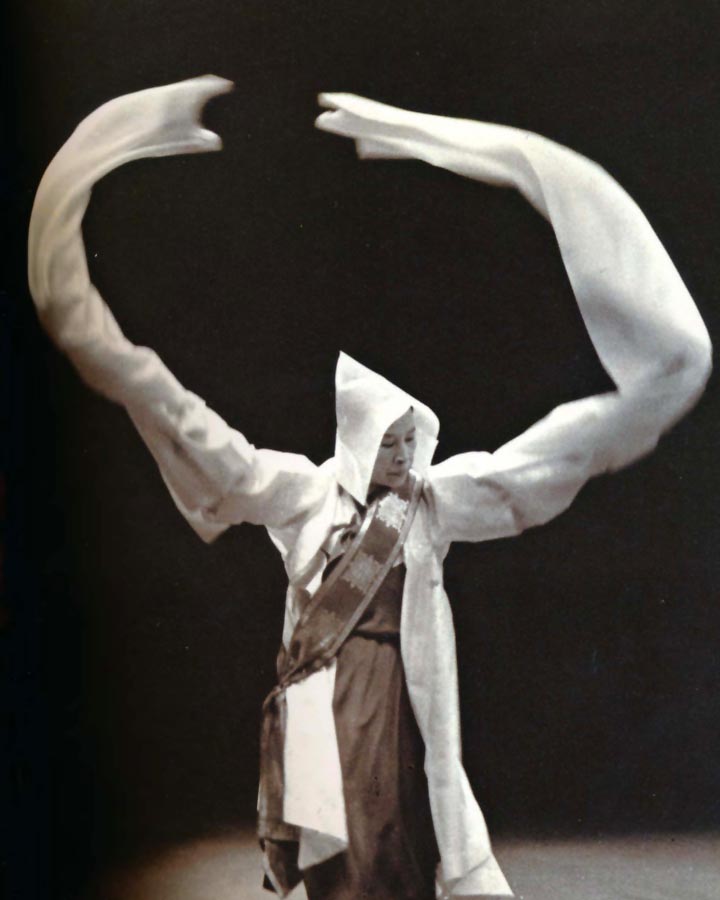

Folk songs and ritual music served as key inspirations for many of the salient genres and repertoires of the Korean performance tradition currently preserved as Korea’s intangible cultural assets. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Korean performative culture encountered an influx of Western cultural forms. The introduction of proscenium stage and other stage landscapes effected major transformations to native performance practices. The performances that had been held at worksites, outdoors, and at kisaeng (traditional female entertainers) houses, had to be reframed for the modern stage and mise en scène. Thus collected, they came to be known as the “Korean traditional performances” in the twentieth century and beyond.

Click or tap on each of the images below to discover more about each individual performance tradition.

is housed in the Department of East

Asian Languages and Literatures (DEALL).

(614) 292-5816

Email: deall@osu.edu

Website: Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures